Normally, the answer would be technical or organisational, but a new type of ransomware called Maze seems to have stirred up a very different response in one of its recent victims – bring in the lawyers and try to sue the gang behind it. As SophosLabs explains in the new report, the Maze crew was one of the first ransomware gangs out there to turn to a combination of blackmail and extortion, demanding that victims pay what is effectively hush money as well as a kidnap ransom.

What’s the most effective way to fight back against a large ransomware attack?

Normally, the answer would be technical or organisational, but a new type of ransomware called Maze seems to have stirred up a very different response in one of its recent victims – bring in the lawyers and try to sue the gang behind it.

The victim this time was US cable and wire manufacturer Southwire, which last week filed a civil suit against Maze’s mysterious makers in Georgia Federal court.

This mentions a big attack involving Maze, which we know from the company’s Twitter account happened on 11 December 2019.

Given that the attackers are unknown – referred to only as “John Doe” in legal filings – this might sound like a fool’s errand. But it seems it is the way the ‘Maze Crew’ attempted to extort Southwire that led to such unorthodox tactics.

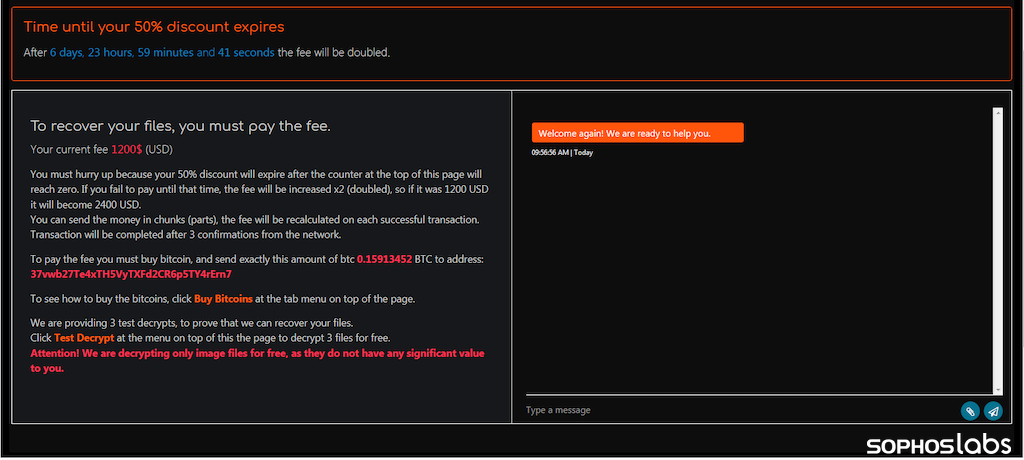

According to Bleeping Computer, the sum demanded from Southwire was 850 Bitcoins, equivalent to around $6 million.

That sounds like a lot to supply some encryption keys to unlock scrambled data, but the demand was backed by a second and more sinister threat – if the sum wasn’t paid the data would be released publicly.

That ransomware attackers can steal as well as encrypt data isn’t a new phenomenon but the possibility that sensitive data might be revealed to the world is potentially more damaging than any short-term disruption caused by the malware.

And yet, despite the seriousness of this threat, it seems that Southwire declined to pay.

Circling the wagons

Sophos Maze Ransomware Download

To understand this defiance, consider other recent Maze incidents in which the Maze gang released samples of the stolen data to media, and set up a special website to publish it.

Southwire would have known this was likely to happen because the attackers reportedly name-checked that they’d released the data from another victim as part of their ransom pitch.

The same website was eventually used to publish some of Southwire’s data, with further releases promised.

As Southwire’s incident website explains, at that point the company decided to go after the website, gaining a court order in Ireland on 31 December to have the domain and the data on it taken down.

Will this deter Maze from releasing he data elsewhere? Probably not. But the mere fact that three sizeable victims have dared them to release breached data isn’t exactly a great advert for the ransomware’s effectiveness.

It’s remotely possible that the Maze gang left clues as to their origins when they registered the domain, hence the involvement of lawyers that might unmask their identities.

Sophos Maze Ransomware Protection

FBI warning

It’s since emerged that with less-than-ideal timing the FBI issued a non-public warning to US businesses on 23 December 2019 warning that the Maze gang was on the prowl.

Sophos Maze Ransomware Download

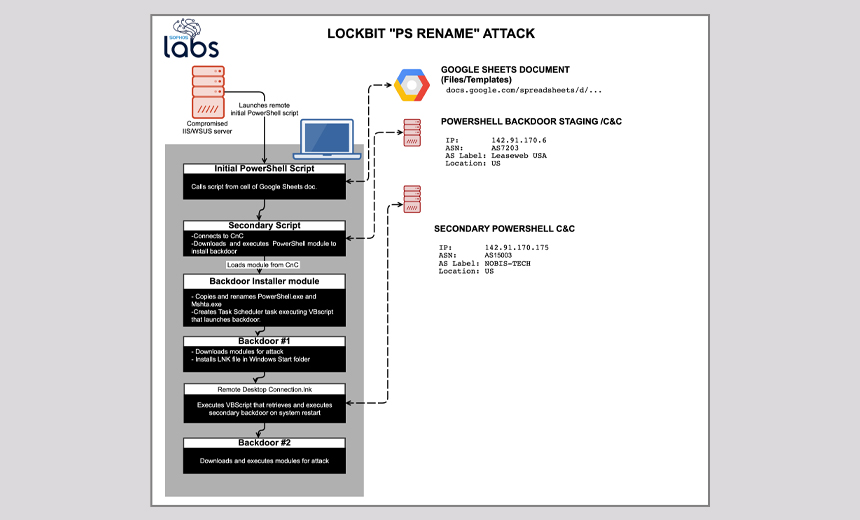

This does at least offer important information on the ways Maze infects targets using boobytrapped macros inside Word documents pretending to come from governments, including the use of exploits against flaws in Internet Explorer (CVE-2018-8174) and Adobe Flash (CVE-2018-15982, CVE-2018-4878) where available patches haven’t been applied.

The FBI advises not to pay Maze’s ransoms because doing so would not guarantee the recovery of data, nor the destruction of stolen data.

Whether that’s correct or not, the die has been cast – just when you think ransomware crooks have worn out every trick they use to get paid, they hit on a new one. Data exposure driven by ransomware could be the next big wave.

The gang responsible for the Maze ransomware family conducted an attack in which they distributed their malware payload inside of a virtual machine (VM).

Sophos’ Managed Threat Response (MTR) observed the technique in action while investigating an attack that occurred back in July 2020.

In that incident, the attackers packaged the ransomware payload inside of a Windows .msi installer file that was more than 700MB in size and distributed it onto the VM’s virtual hard drive.

An investigation into the attack revealed that the malicious actors had been present on the targeted organization’s network for at least six days prior to distributing their ransomware payload. During that period, they had built lists of internal IP addresses, used one of the organization’s domain controller servers and exfiltrated information to their data leaks site.

This dwell time could explain the existence of certain configurations of the Maze-delivered VM. As quoted by Sophos’ MTR in its research:

The virtual machine was, apparently, configured in advance by someone who knew something about the victim’s network, because its configuration file (“micro.xml”) maps two drive letters that are used as shared network drives in this particular organization, presumably so it can encrypt the files on those shares as well as on the local machine. It also creates a folder in C:SDRSMLINK and shares this folder with the rest of the network.

The campaign described above wasn’t the first instance in which attackers have delivered ransomware inside a virtual machine. Back in May 2020, Sophos’ MTR spotted the Ragnar Locker crypto-malware family pull the same trick.

The virtual machine in that attack ran Windows XP as opposed to the Windows 7 instance on the VM containing Maze. Furthermore, the latter VM was larger in size in order to support additional functionality.

This technique highlights the need for organizations to defend themselves against a ransomware infection. They can do so by working to prevent a crypto-malware attack in the first place.